US inflation reached a record growth trajectory since 1982, adding +0.6% m/m and +7.6% y/y in January against the forecasted +0.5% and +7.3%. At the same time, yields sharply increased – 10-year UST exceeded 2% for the first time since August 2019, but as usual, the US dollar showed mixed dynamics in the currency market. The demand for it did not grow.

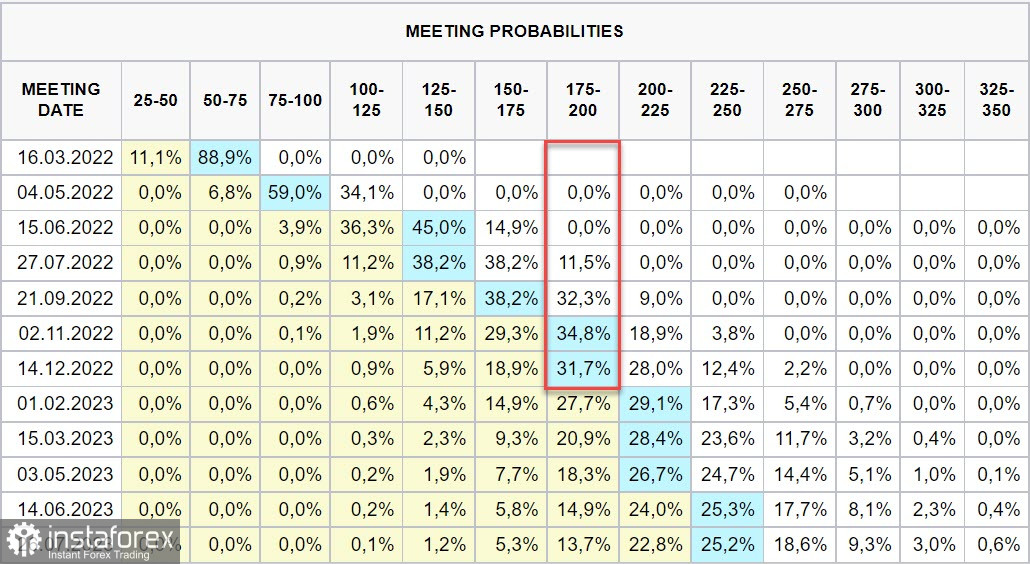

Higher-than-expected inflation has led to an increase in hawkish rhetoric – Bullard insists on raising the rate by 100p by July. The market sees a 99% probability of an increase in March by 0.5% at once (compare with the probability of 30% just a day ago). By the end of the year, we may see the transition of the federal rate to the range of 175/200p.

In addition, Bullard also announced the possibility of raising the rate without waiting for the Fed meeting, and such a comment looks frankly panicky.

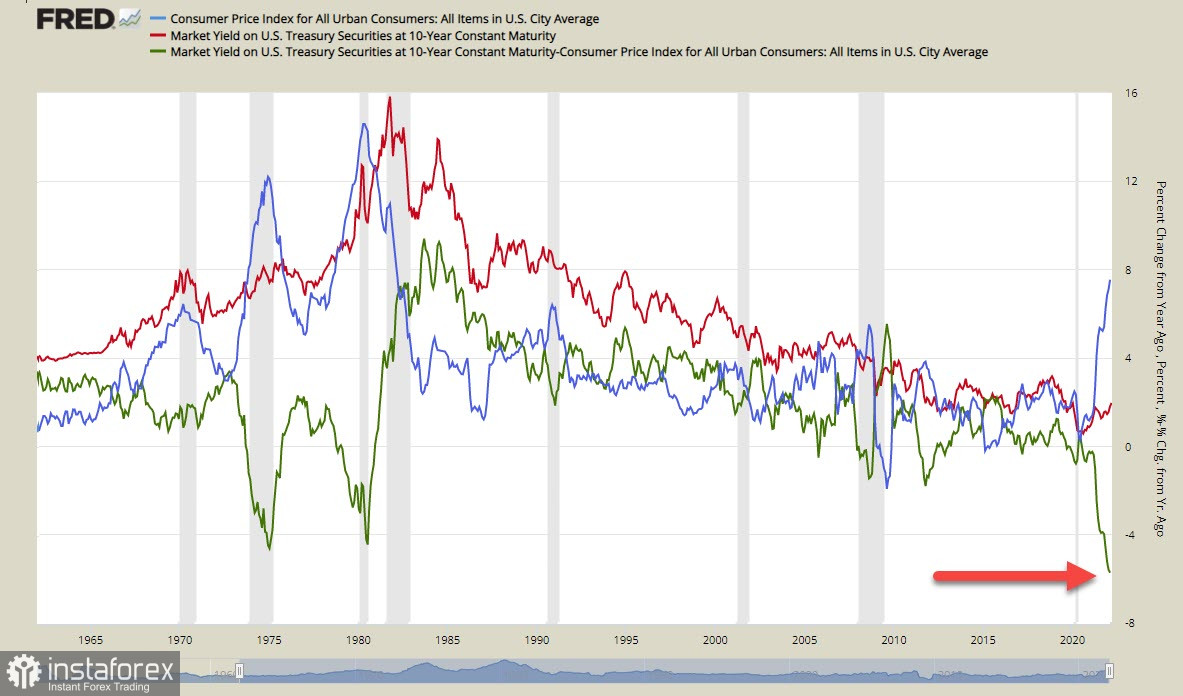

To assess the scale of the problem, one can look at the dynamics of the real yield of 10-year UST. It can be seen in the chart below (green line) that real returns are currently at historic lows and already lower than they were during the 1970-82 crisis. The difference between the current situation and the situation 40 years ago is that the Fed had all the necessary tools to manage monetary policy at that time, but now, there are significantly fewer tools.

All the Fed can do in this situation is to aggressively raise rates. If two weeks ago, the market saw a four rate hike this year and the first increase in March by 0.25%, now it tends to 6-7 increases with the first step of 0.5%. It should be noted that even such aggressive actions on the Fed's part will not be able to raise real yields from the negative zone.

Why did inflation turn out to be so high? There are different estimates. Some say that consumer behavior has fully adapted to the pandemic – the Omicron strain was softer than expected and has stopped restraining prices, while others say that COVID-19 has caused serious damage to supply chains, and that's exactly the point.

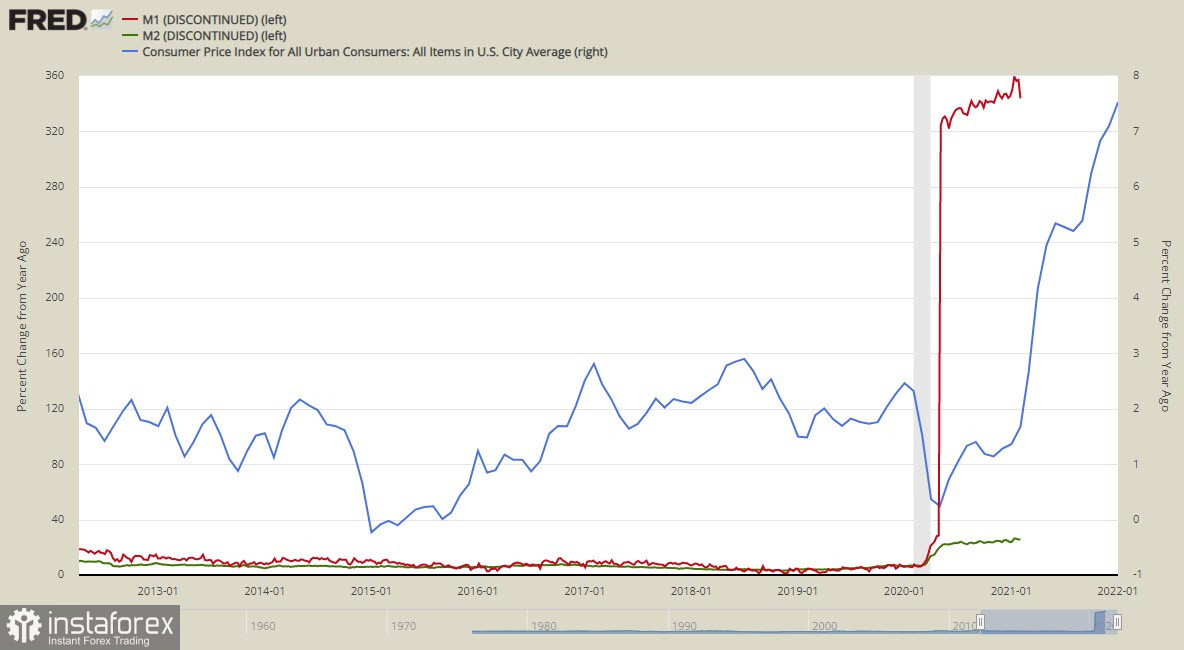

Perhaps, the reason is on the surface? In May 2020, there was a sharp surge in the M1 monetary aggregate. This is a technical adjustment because the M1 aggregate, which is money and highly liquid assets, was added to the component from M2 that was not previously included in the calculation, namely savings deposits. On April 24, restrictions on the number of transactions or withdrawals allowed in savings deposit accounts were lifted, allowing banks to no longer hold reserves for deposits. These funds went to the market in search of profitability.

The growth of the M1 monetary aggregate from $4.8 trillion to $16.3 trillion caused a sharp increase in inflation. Will the Fed be able to stop this growth with an aggressive rate hike? This is theoretically possible, but only if real interest rates are raised. For the real yield to become above zero, it is necessary to raise the rate above the inflation rate, which is absolutely impossible.

The Fed will not be able to raise the discount rate above 2-3% since the problem of servicing the accumulated debt will create such a hole in the US budget, which will have to be compensated by new loans at a much higher rate than now, which will create a crisis of confidence in the US dollar.

Consequently, the Fed, in addition to raising the rate, needs to invent some other tool that will lower inflation expectations and allow inflation to return to the target. If the Fed manages to solve this non-trivial task and surprise the markets, then the US dollar will resume growth across the spectrum of the market, as dollar-denominated financial instruments will have good prospects for growth. On the contrary, if the Fed is unable to offer anything other than an aggressive rate hike, then this will only have a short-term effect, without withdrawing excess liquidity. Inflation will continue to rise despite the Fed's best efforts, and the US dollar will begin to sell off, as investors will begin a mass exodus from assets in search of positive returns.