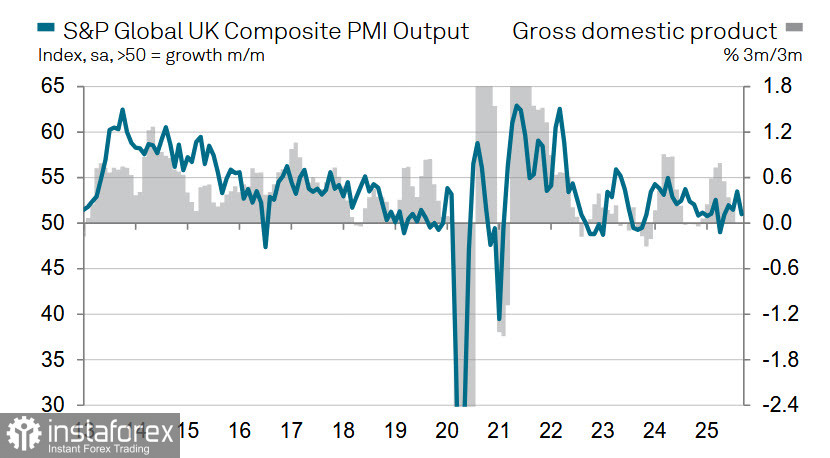

The second estimate of UK GDP confirmed 0.3% growth for Q2, but the composition of growth reveals a troubling trend—stagnant consumer spending was offset by increases in government expenditures and a widening current account deficit. Expectations of accelerated GDP growth in Q3 remain low, as the composite PMI index fell in September to a four-month low of 51 points. The manufacturing PMI hit a five-month low and remained firmly in contraction territory.

Structural problems are building in the UK economy and are increasingly impacting its resilience. Public borrowing in August significantly exceeded forecasts, with the budget deficit rising to £18 billion—a five-year high. Over just five months of the fiscal year, the deficit reached £83.8 billion, the second-worst result since 1993. According to opposition shadow chancellor Mel Stride, "The Chancellor has lost control of the public finances."

This is a fundamental issue, and there is no easy solution. The debt-to-GDP ratio is rising, and what's more crucial than the absolute ratio—now at 100%—is the difference between the effective interest rate on government debt and the nominal GDP growth rate. If the interest rate is higher, the government must run a primary surplus; otherwise, the debt grows rapidly. Currently, the effective interest rate on government debt in the UK, considering the average maturity of government bonds, is approaching 4%, while the nominal GDP growth rate is around 5% annually. However, if inflation falls toward the Bank of England's 2% target, nominal GDP will decline to about 3.0–3.5%. This would require a primary surplus of around 1.0–1.5% to maintain debt stability. Without it, debt could accelerate and eventually undermine overall financial stability.

But there is no surplus—nor is one possible in the current environment. The UK's total budget deficit accounts for roughly 5% of GDP, with the primary deficit at around 2%. This means the revenue side needs a significant boost, which the government is attempting to achieve through fiscal reforms. In the meantime, however, the BoE must also lower interest rates to reduce the effective cost of borrowing.

Hence, it's clear the Bank is being forced to maintain a dovish stance—even amid rising inflation. While the inflation surge is officially deemed "temporary," the markets are focused on more critical long-term issues than inflation itself.

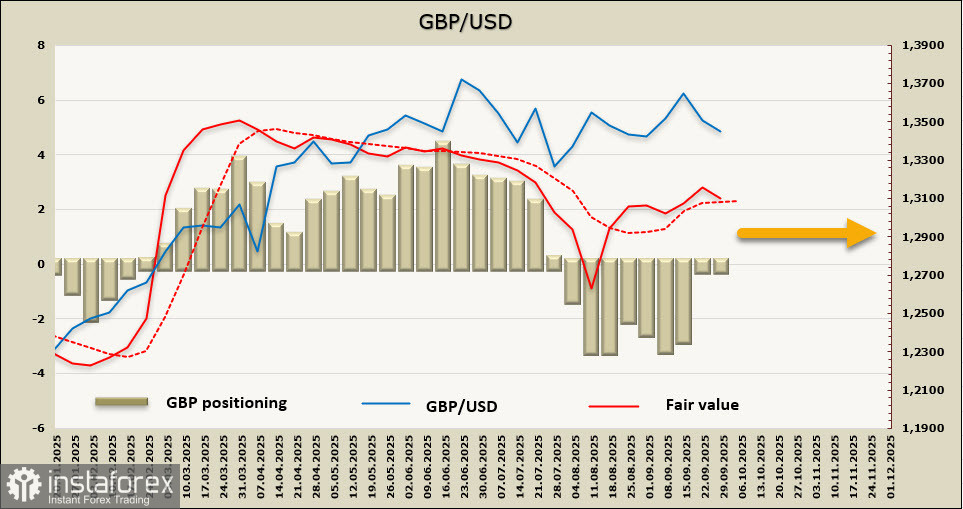

Under these circumstances, the pound is unlikely to remain strong. A strong currency undermines budget revenues and exacerbates the deficit.

Speculative positioning on the pound has shifted from moderately bearish to neutral. The net short position declined by £0.4 billion over the reporting week, standing at a marginal -£166 million. The calculated fair value remains above the long-term average but has now turned downward.

Last week, we assumed the pound would retain a bullish tone and, after a correction, would attempt to challenge resistance at 1.3787. However, this scenario now looks rather unlikely. The market has shifted into a sideways range. Support is seen at 1.3320/30; if this level fails to hold, bearish pressure could intensify. On the upside, the pound is capped near 1.3725, but chances of revisiting that level currently appear slim.